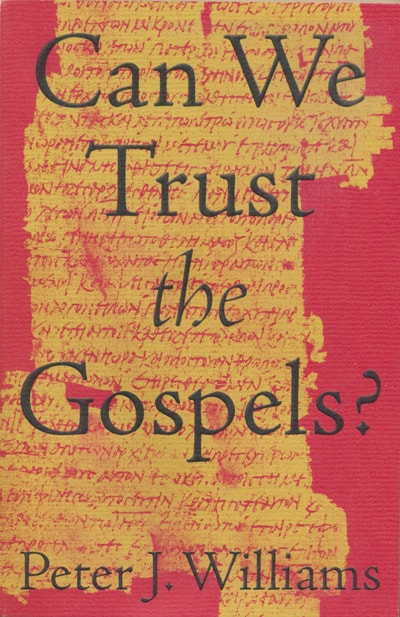

Book Review: Can We Trust the Gospels by Peter J. Williams

The writings of Dr Bart Ehrman have undoubtedly had a very negative effect on the faith of many. It is widely reported that many young Christians, exposed to his teachings, have abandoned their faith by the time that they graduate from Colleges or University. Christian scholars have responded with numerous books offering both answers to Ehrman’s objections and new research which serves to demonstrate the credibility of the Gospel accounts of Jesus. I have previously reviewed another book in this genre, The Heresy of Orthodoxy, and was delighted receive a pre-publication of Peter J. Williams book, Can We Trust the Gospels? from the publisher.

The writings of Dr Bart Ehrman have undoubtedly had a very negative effect on the faith of many. It is widely reported that many young Christians, exposed to his teachings, have abandoned their faith by the time that they graduate from Colleges or University. Christian scholars have responded with numerous books offering both answers to Ehrman’s objections and new research which serves to demonstrate the credibility of the Gospel accounts of Jesus. I have previously reviewed another book in this genre, The Heresy of Orthodoxy, and was delighted receive a pre-publication of Peter J. Williams book, Can We Trust the Gospels? from the publisher.

This is a very short book (153 pages including indexes), but one that covers a tremendous amount of ground, at the same time condensing a huge amount of scholarly research. This book is not just a good summary of a complex subject, but adds new insights along the way, based on first-hand research, as I will mention again later.

The book is laid out as follows:

- What do Non-Christian Sources Say?

- What Are the Four Gospels?

- Did the Gospel Authors Know Their Stuff?

- Undesigned Coincidences

- Do We Have Jesus’s Actual Words?

- Has the Text Changed?

- What about Contradictions?

- Who Would Make All This Up?

1. What do Non-Christian Sources Say?

Chapter 1 discusses the importance of the writings of Tacitus (pp.18-24), Pliny the Younger (pp.24-31) and Josephus (pp.31-35), and demonstrates how quickly the Gospel spread across the Empire. It also notes how key teachings of the early Christians, such as belief in the Deity of Christ, were recognised at an early date by non-Christian observers (pp.28-31).

2. What Are the Four Gospels?

Introduces the Gospels, their dating, interdependence, and traditionally ascribed authorship. Arguments supporting the traditional authorship is presented in later chapters. I particularly liked the argument for Matthew the Tax Collector based on that Gospel’s unique interest in financial matters (pp.82-83). Here, as throughout the book, the judicious use of footnotes allows interested readers to find further information. In this chapter I found the reference to Brant Pitre’s book, The Case for Jesus (p.43, n.9) particularly helpful, having repeatedly been assured by people, who ought to have known better, that the Gospels were all originally anonymous.

3. Did the Gospel Authors Know Their Stuff?

I have to admit that, having heard Peter William’s Bible and Church Lecture in London a few years ago, I was particularly interested to see the argument he presented there written down and developed and was not disappointed. There are numerous charts demonstrating the Gospel writers intimate knowledge of Palestinian geography (pp.52-57), hydrology (pp.57-58), roads (pp.58-61), and even Gardens (pp.61-62). Here I liked the point about the writers’ descriptions of Galilee. While Matthew, Mark and John all call it a sea, Williams points out that…

Luke is rather different. It uses the word sea only three times and never to reference a particular body of water. If, as is traditionally thought, Luke came from Antioch on the Orontes, not far from the Mediterranean, he certainly would not have thought of the tiny Sea of Galilee as the sea. He just calls it “the lake”. [p.58. Underlining italics in original]

The next section is based on Richard Bauckham’s research on personal names [pp.64-78, esp. p.64, n.28), showing how the Gospels’ use of disambiguation correlates very closely with the relative popularity of names in 1st Century Palestine, but not outside of that time or location. Combined with further arguments based on the writer’s knowledge of Jewish customs (pp.78-81), botany (pp.81-82), finance (pp.82-83 – already referred to above) and languages they make a strong cumulative case for authenticity.

4. Undesigned Coincidences

Williams then turns to Lydia McGrew’s development of J.J. Blunt’s Undesigned Coincidences, giving several examples of how the Gospels include incidental details that someone without eyewitness information could not possible have known about. It discusses Mary and Martha’s personalities (pp.88-91), the feeding of the 5,000 (pp.91-94) noting the significance of the grass. Having worked in Nepal, where grass withers very quickly after the rains stops, I appreciated the argument here. The final coincidence covers the account in the Gospels and Josephus concerning Herod Antipas (p.94-96).

5. Do We Have Jesus’s Actual Words?

Here is discussed the difference between 1st Century and modern ideas of what constitutes an accurate quotation and it is argued that the disciples of Jesus would have been quite capable of passing on accurate traditions about him. The languages in which Jesus spoke are discussed (pp.106-109). He notes:

Language contact means that a Jew speaking in Greek to a Jewish audience would plausibly be able to use specificly Aramaic words as recorded in Matthew 5:22 (raka) and 6:24 (mamona), both of which occur in the Sermon on the Mount. Also, by the time of Jesus many Greek words had been loaned into Aramaic. If Jesus originally told the parable of the prodical son in Aramaic, there is no reason why he could not have used some of the very vocabulary found in our Greek version, such as the Greek word symphonia (“music,” Luke 15:25), which by then had been adopted into Aramaic. Jesus presumably would have spoken Greek to the Greeks in John 12:23, with the Centurion in Matthew 8:5-13, with a Greek woman in Mark 7:26, and possible also with the Herodians in Mark 12:13.” [p.109. Underlining italics in original]

6. Has the Text Changed?

In this chapter, Williams draws, not for the first time (p.81, p.52), on his own research and work in textual criticism to argue for the veracity of the Greek text of the Gospels. Again, the rapid spread of the church throughout the gospels is said to make it impossible for major doctrine changing textual variants to be deliberately introduced (pp.120-122).

7. What about Contradictions?

This chapter is very brief and focuses on formal contradictions in the text. These are deliberate and “…show that the author is more interested in encouraging people to read deeply than in satisfying those who would find fault.” (p.127).

8. Who Would Make All This Up?

The final chapter concludes that the simplest and best solution that explains the Gospels as we now have them is that they are what they claim to be.

Who Should Read This Book?

I think that anyone who has been challenged by the work of critics such as Bart Ehrman would find this book of great help. It would also be good to place it in the hands of non-Christians who are considering the claims of Jesus and have doubts about the Gospels. Personally, I found myself encouraged to dive into the suggested further reading (p.13, n.1), but most of all to read the Gospels again with a fresh appreciation of their depth, accuracy and sophistication.

Book Details

Peter J. Williams, Can We Trust the Gospels? Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2018. Pbk. ISBN-13: 978-1-4335-5295-3. pp.153.

One Comment

Comments are closed.